Maduwongga Phonology

Table of Contents

Introduction

This phonology is based on 2017 recordings undertaken by the Goldfields Aboriginal Language Centre (GALC) with speaker of the Maduwongga language Anne Joyce Nudding. Additional historical material has also been used to reference GALC recordings such as Jules Garnier, Vocabulary of the Indigenous People of Western Australia; Norman Barnett Tindale, Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits and Proper Names (1974).

A phonology is a document that catalogues the sounds of a language, how these sounds are produced in the mouth and the alphabet used to represent the sounds. Letters of the Roman alphabet are used to represent the sounds in this language. However, some sounds found in Maduwongga language do not correspond to the English letter sounds and therefore sometimes two letters are used to represent one phoneme (sound) such as ‘ly’ which represents the sound found in the English word, million, and the Maduwongga word lalypu ‘sleeping hollow’.

This phonology document also explains phonological features found in words of the Maduwongga language such as the vowels, consonants, consonant clusters, syllables and stress patterns.

The morphology, sentence structure, suffixes and adverbs will be addressed in a forthcoming sketch grammar of this language. There is more than 20 hours of recording with the speaker and more than 500 words and around one hundred sentences entered into a lexical database. Some Maduwongga people are known to have lived in Edjudina Station, thus, further research on Edjudina Station will be undertaken to see if further historical language material can be located.

The ‘Consonant Phonetic Description’ and ‘Minimal Pair’ sections of this paper contain sound files. To hear the pronunciations, click on the word.

The spelling of the language, Maduwongga, does not reflect the current spelling system for the language. The language has been written this way in the past and continues to be written this way until speakers indicate that the current orthography should be used for the name. Sometimes language name spellings are fixed for sociolinguistic reasons and may remain so.

This Phonology

1. Orthography

Linguists and language speakers jointly decide which letters best represent the sounds of a language. This is done by detailed phonemic analysis of each sound, discussion with speakers and a decision is made on the orthography or alphabet to use for a language. The sound is then best matched to the Roman alphabet or a combination of two letters are chosen to represent the sound, such as ‘ly’ in the word lalypu ‘sleeping hollow’. This document will explain the choices made and the reasons for making them.

One of the features of this language is that every sound is not found in every place in a word. Some sounds are only found at the start of a word or middle of a word and some are only found in the middle or the end of a word.

Some sounds are more voiced at the start of a word and less voiced in the middle or end of a word. The letters ‘k’, ‘p’ and ‘t’ have been chosen to represent the sounds that vary from the voiced ‘g’, ‘b’ and ‘d’ to the unvoiced ‘k’, ‘p’ and ‘t’. In English, these phonemes are heard and used as separate sounds. However, in this language, they are heard and used as single phonemes with more or less voicing. The amount of voicing is, generally, stronger at the start of the word and therefore they are heard as the English phonemes ‘g’, ‘b’ and ‘d’ where as less voicing is heard word central or word final and they are heard as the English ‘k’, ‘p’ and ‘t’.

Voiced and unvoiced phonemes

This selection of 100 words have been used to calculate the percentage of voiced and unvoiced ‘p, t, k’ phonemes.

The percentage of voiced versus unvoiced phoneme use is:

1. karlaya ‘emu’ 2. kanyirni ‘holding’ 3. kampatarra ‘flame up’ 4. kultutu ‘heart’ 5. kangkarra ‘on top’ 6. kaparli ‘grandmother’ 7. karkapun ‘tidy up’ 8. kaltu ‘cut’ 9. kumpur ‘urine’ 10. kana ‘awake’ 11. karkarri ‘drunk’ 12. kuka ‘meat’ 13. kutala ‘cook’ 14. kuri ‘wife’ 15. kakiliru ‘shiny’ 16. nyaku ‘look’ 17. pakala ‘get up’ 18. pakurin ‘tired’ 19. parakarri ‘fall’ 20. yiiku ‘face’ 21. nayuku ‘my’ 22. ngalkanku ‘fast’ 23. nurraku ‘your’ 24. ruukuli ‘think’ 25. waka ‘stab’ 26. juki juki ‘chick’ 27. tjikil ‘dry’ 28. paarpakan ‘flying’ 29. pakarnala ‘get up on something’ 30. pangkanurru ‘over’ 31. murunpu ‘bush’ 32. puyu ‘smoke’ 33. piirrka ‘cockatoo’ 34. pika ‘sick’ 35. kulila ‘listen’ | 36. panpanparala ‘little bird’ 37. pantjura ‘swim’ 38. parna ‘groud’ 39. parni ‘smell’ 40. pulpa ‘hole’ 41. papul ‘basin’ 42. papa ‘dog’ 43. papurrpan ‘ceremony’ 44. pupa ‘bend’ 45. japirn ‘lizard’ 46. jinapuka ‘shoes’ 47. nampirli ‘bread’ 48. nampurla ‘dive’ 49. nampu ‘brain’ 50. nyalpa ‘old person’ 51. lupu ‘loop’ 52. tali ‘sandhill’ 53. tanapini ‘mob’ 54. tarka ‘bone’ 55. tiki ‘drink’ 56. tingurru ‘maybe’ 57. tarpa ‘chin’ 58. tarutu ‘heavy’ 59. tawala ‘dig’ 60. timpeteri ‘knife’ 61. tunti ‘cave’ 62. tanti ‘egg’ 63. kata ‘head’ 64. kuntili ‘aunty’ 65. jitu ‘still’ 66. wanti ‘stop’ 67. yalta ‘cold’ 68. yultu ‘car’ 69. jintu ‘sun’ 70. nanta ‘sneaking’ | 71. nati ‘do not’ 72. nyuntu ‘kissing’ 73. kartala ‘break’ 74. kultu ‘back’ 75. yuntu ‘throat’ 76. ngunti ‘neck’ 77. jintutarra ‘hairy’ 78. yiltan ‘steak-like meat’ 79. tarrun ‘berry’ 80. wati ‘initiated man’ 81. puntu ‘man’ 82. nantu ‘same’ 83. manta ‘money’ 84. kakarra ‘east’ 85. kali ‘boomerang’ 86. kana ‘awake’ 87. lipinu ‘exit’ 88. mapirn ‘witch doctor’ 89. munta ‘close’ 90. nyitila ‘smear’ 91. para ‘down’ 92. patala ‘bite’ 93. yurnapa ‘rotten’ 94. yikarin ‘laughing’ 95. yapu ‘rock’ 96. kapi ‘water’ 97. wilkara ‘lift’ 98. wipu ‘tail’ 99. tili flame 100. tipari ‘cut on man’s chest’ |

Percentages of voiced versus unvoiced phoneme use

Bilabial Plosive (voiced b, unvoiced p) | Dental Stop (voiced d, unvoiced t) | Velar-Plosive (voiced g, unvoiced k) | Total | % | ||||||

| Syllable | Voiced (b) | Unvoiced (p) | Syllable | Voiced (d) | Unvoiced (t) | Syllable | Voiced (g) | Unvoiced (k) | ||

| Initial | 20 | 0 | Initial | 14 | 0 | Initial | 24 | 0 | 58 voiced 0 unvoiced | 38.67% |

| Medial | 0 | 10 | Medial | 0 | 9 | Medial | 0 | 10 | 29 unvoiced 0 voiced | 19.33% |

| Final or more | 0 | 21 | Final or more | 0 | 26 | Final or more | 0 | 16 | 63 unvoiced 0 voiced | 42% |

| Total | 20 | 31 | Total | 14 | 35 | Total | 24 | 26 | 150 phonemes | 100% |

The outcomes of the comparison of unvoiced and voiced phonemes use are:

- 100% (58 phonemes) of the voiced phonemes are found in initial syllables.

- 0% of phonemes are unvoiced initial.

- 33 % (29 phonemes) of the unvoiced phonemes are medial.

- 0% of phonemes are voiced medial.

- 42% (63 phonemes) of the unvoiced phonemes are final.

- 0% of phonemes are voiced final.

2. Vowels

This language has three short vowel sounds a, i, u and three long vowel sounds aa [a:], ii [i:], uu [u:]. The vowels sounds do not change and remain constant.

The language is rhotic and therefore vowels are rhotacized.

The phonemes represented by ‘y’ and ‘w’ are semi-vowels. These are pronounced the same as in English. However, at the start of a word, these semi-vowels may not be pronounced such as in the word yini ‘name’, which is pronounced ‘ini’. In this circumstance the ‘y’ operates as a glide.

2.1 Vowel Table

a as in English ‘mother’

aa as in English ‘father’

i as in English ‘pin’

ii as in English ‘pin’ but held longer

u as in English ‘put’

uu as in English ‘put’ but held longer

| front | central | back | |

| high | i [i], ii [i:] | u [u], uu [u:] | |

| low | a [a], aa [a:] |

Maduwongga vowel inventory

2.2 Short Vowels

Short vowels may appear in any syllable of a word. There are no restrictions on which vowels may appear next to which consonant; that is, any vowel may precede any consonant or follow any consonant.

2.3 Long Vowels

Long vowels occur in 16 of 500 words in the 2017 wordlist. 5 out of 16 long vowels do not have natural speech recording as of December 2017. Almost all long vowels occur in the first syllable of a word. When the ii [i:] sound comes after a laminodental nasal ‘ny’ it sounds like ‘e’ like in English ‘bet’.

- kaanmarra ‘calm’

- paarpakan ‘flying’

- ruukulila ‘think’

- yiiku ‘face’

- nyiinyi ‘finch’

Examples for long vowels with no natural speech recording are:

- nguurntjunu ‘intimidated’

- yaaltji ‘what’

- waarniny ‘creek’

2.4 Vowel Prosody

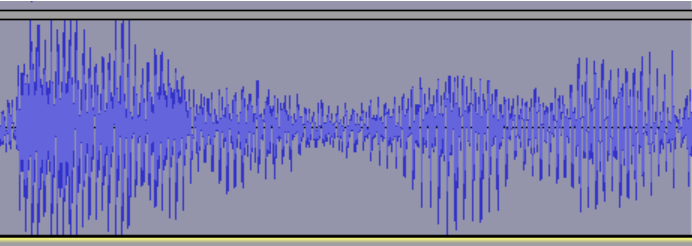

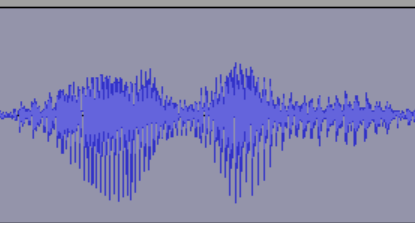

The speaker uses long vowels when she is telling a story which shows that it is neither an individual phonetic segment nor a formal use. As in the example below, the speaker emphasizes time to say the travel took a long time by lengthening the pronunciation of the vowel on maapitjanu.

- ‘Yultungka pitjanu maapitjanuu, yultu kampatarranu.’

yultu-ngka pitja-nu maa-pitja-nu+u yultu kampa-tarra-nu

car+LOC go+PAST contranym+go+PAST+EMPH car burn+ABL+PAST

in the car came went car flamed up

‘We went and went for a long distance and all of a sudden the car caught on fire.’

2.5 Vowel Harmony

Vowel harmony in the long vowels aa [a:] is followed by ‘a’ or ‘i’ phoneme; ii [i:] is followed by ‘u’ or ‘a’ phoneme; uu [u:] is followed by ‘u’ or ‘a’ phoneme. However, this may not constitute a formal rule as the long vowels are very rare in the language.

To date, no vowel harmony has been found in short vowels.

3. Consonants

The letters of the English alphabet have been used to represent each consonant phoneme in this language. However, digraphs are used to represent phonemes not found or very uncommon in the English language. For example, the alveopalatal lateral in the centre of the word million is common in this language and represented with the digraph ‘ly’ such as in the word ‘lalypu’ sleeping hollow.

These phonemes remain constant, as for the vowels. That is, the sound they produce does not change.

Some consonant clusters can be found in these words and these are described in a later chapter in this phonology document.

This language has two rhotic or r-like sounds, a retroflex approximant such as found in the American English ‘r’ and a trill or tap ‘rr’ which is found in the Scottish English.

3.1 Consonants Table

| Place of Articulation |

Bilabial |

Dental |

Alveolar |

Retroflex |

Alveopalatal |

Velar |

| Manner of Articulation | ||||||

Stops | p | th | t | rt | tj | k |

Nasals | m | n | m | ny | ng | |

Laterals | l | rl | ly | |||

Rhotics | rr | r | ||||

Glides | w | y | ||||

Approximants | j |

| Place of Articulation |

Bilabial |

Dental |

Alveolar |

Retroflex |

Alveopalatal |

Velar |

| Manner of Articulation | ||||||

Stops | p | (th) | t | rt | (t)j | k |

Nasals | m | n | m | ny | ng | |

Laterals | l | rl | ly | |||

Rhotics | rr | r | ||||

Glides | w | y | ||||

Approximants | j |

Peripheral and Coronal Consonant Description

Peripherals (non-coronal consonants): Articulated at the extremes of the mouth, i.e. labials and velars.

Coronals: Articulated with the flexible part of tongue. In Australian languages, the coronal consonants can be divided into apical (using the tip of tongue) and laminal (using blade of tongue).

3.2 Consonant Phonetic Description

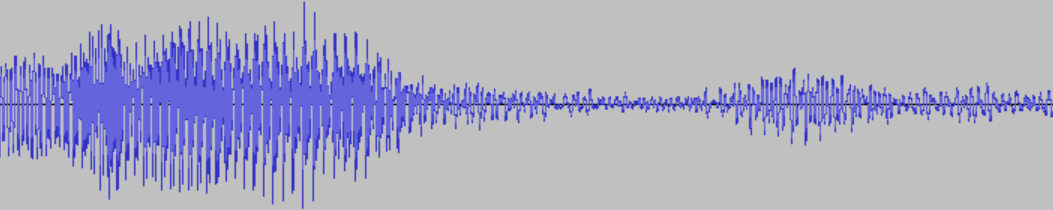

3.2.1 Bilabial Stops p

‘p’ as in Standard Australian English (SAE) ‘pin’. This phoneme is voiced in word initials and unvoiced in word medial.

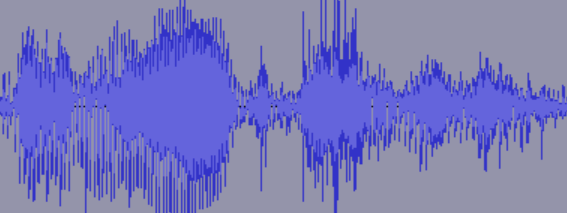

paarpakan ‘flying’ Click on the word to hear it.

3.2.2 Bilabial Nasal m

‘m’ as in SAE mouse.

milji ‘finger nail’ Click on the word to hear it.

3.2.3 Bilabial Glides w

‘w’ as in SAE ‘won’. These glides or semivowels are phonetically similar to vowels, but functions as consonants.

maawarinkarrin ‘arrived’ Click on the word to hear it.

3.2.5 Alveolar Stops t

‘t’ as in SAE ‘top’. This phoneme is voiced in the word initial and unvoiced in the word medial.

tawala ‘dig’ Click on the word to hear it.

3.2.6 Alveolar Nasal n

‘n’ as in SAE net.

nakurla ‘looking’ Click on the word to hear it.

3.2.7 Alveolar Lateral l

‘l’ as in SAE ‘light.

lalya ‘empty’ Click on the word to hear it.

3.2.8 Alveolar Rhotic rr

‘rr’ as in Scottish English ‘bairn’. This phoneme appears in the word medial and final syllable.

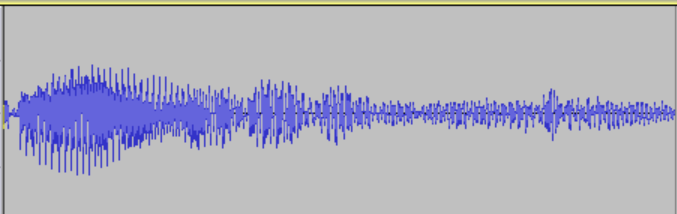

yakarri ‘headband’ Click on the word to hear it.

3.2.9 Retroflex Stop rt

‘rt’ as in American English ‘cart’. This phoneme appears in the word medial and final syllable.

nirtila ‘smear’ Click on the word to hear it.

3.2.10 Retroflex Nasal rn

As in American English ‘barn’. This phoneme appears in the word medial and final syllable.

parnti ‘smell’ Click on the word to hear it.

3.2.11 Retroflex Lateral rl

As in American English ‘curl’. This phoneme appears in the word medial and final syllable.

yarlji ‘how is it?’ Click on the word to hear it.

3.2.12 Retroflex Rhotic r

As in American English ‘car’. This phoneme is always retroflexed.

kurta ‘brother’ Click on the word to hear it.

3.2.13 Alveopalatal Approximant j

As in SAE ‘jar’. The speaker uses very distinct alveopalatal approximate ‘j’ and alveopalatal stop ‘tj. ‘j’ phoneme occurs in 16 words with 12 initial and 4 medial; ‘tj’ phoneme occurs in 20 words with 12 initial and 8 medial.

japirn ‘lizard’ Click on the word to hear it.

3.2.14 Alveopalatal Stop tj

Not found in SAE language. The speaker uses very distinct alveopalatal approximate ‘j’ and alveopalatal stop ‘tj. Alveopalatal stop ‘tj’ occurs in 20 words of 500 with 12 initial and 8 medial.

tjitjipirni ‘children’ Click on the word to hear it.

3.2.14 Alveopalatal Nasal ny

As in SAE ‘onion’. Appears in the word initial and medial syllable.

nyiinyi ‘finch’ Click on the word to hear it.

3.2.15 Alveopalatal Lateral ly

As in SAE ‘million’. This phoneme occurs three times in 500 words with natural speech records: lalya ‘empty’; lalypu ‘sleeping hollow’; mulya ‘nose’.

There is one example with no natural speech recording: kantjalykantjaly ‘mushroom’

lalya ‘empty’ Click on the word to hear it.

3.2.16 Alveopalatal Glide y

As in SAE ‘yellow’. This phoneme may be found word initial, medial or final.

maayarlti ‘call’ Click on the word to hear it.

3.2.17 Velar Stop k

As in SAE ‘get’. This phoneme is voiced in the word initial and usually unvoiced in the rest of the word. The second example shows unvoiced ‘k’ in the medial and last syllable.

kurta ‘brother’ Click on the word to hear it.

nakuku ‘look’ Click on the word to hear it.

3.2.18 Velar Nasal ng

As in SAE ‘song’. This phoneme appears word initial and medial. The speaker has not used the sound in the word final position.

ngurnti ‘neck’ Click on the word to hear it.

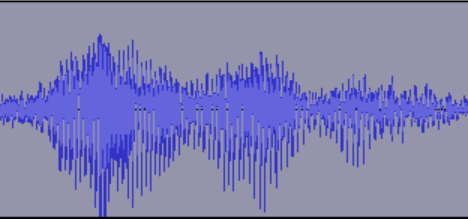

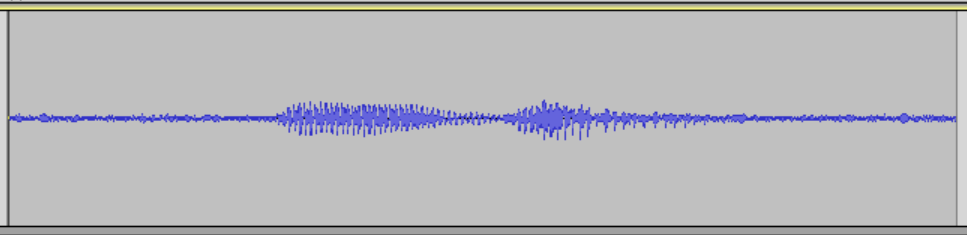

3.3 Dental Stops th

The languages of the Goldfields region use a very similar phonemic system. The main phonemic difference is to be found in the dental stop, which is represented either as ‘tj’ or ‘th’, depending on whether the tongue is apical (tip of the tongue on the back of the teeth) or laminal (blade of the tongue on the back of the teeth). The interdental fricative is heard in speakers of two languages and is represented by ‘th’. However, this is contentious as early linguistic writing of the dental stop was by use of the ‘th’ and speakers who use this sound are literate and/or very elderly with lost teeth. The lack of teeth may have led to sound change that is now being passed down to younger speakers. It may also be possible that the interdental fricative is a contemporary phoneme arising from speakers seeing the words in the written form and hyper correcting.

At the present time the speaker has missing teeth from her upper jaw and that might be the evidence of absence of dental stop ‘th’ and existence of alveolar-palatal stop ‘tj’. However, during the recordings, the speaker did not show any effort to make ‘th’ sound in Maduwongga using her upper gum as she was observed. On the contrary, while she is speaking English, she produces ‘th’ sound with her tongue tip and rims articulate with the upper teeth as in the examples of ‘teeth’ and ‘throw’.

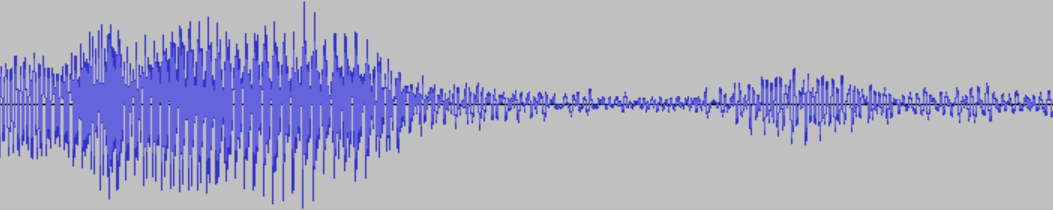

teeth Click on the word to hear it.

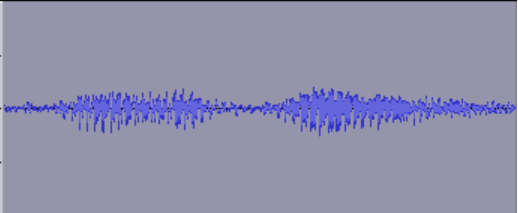

throwing in the fire Click on the word to hear it.

4. Word Structure

4.1 Syllable Structure

The minimum word structure is CV, e.g.

tjaa ‘mouth’ tj/aa = C/V

One example of a CVC word exists:

nyin ‘sit’ = CVC

The most common minimum word pattern is CVCV, e.g.

jina ‘foot’ ji/na = CV/CV

4.2 Word Initial Sounds

The speaker has not used any vowel initial words. There is only one word ‘ilba’ bungarra–sand goanna, from a late speaker’s wife with no natural speech record of it to verify.

Word initial consonants:

j, k, l, m, n, ng, ny, p, r, t, tj, w, y

There are only two words starting with ‘r’ in the current 500 word lexicon.

1. ruukuli ‘think’

2. rawarrin ‘lost the track of time’

The consonant ‘rr’ does not occur word initial.

Initial sounds ‘t’, ‘n’, and ‘l’ are all retroflexed; however, they are not written as ‘rt’, ‘rn’ and ‘rl’.

4.3 Word Final Sounds

There are no restrictions on word final phonemes. Words tend to end with a vowel or may end with the consonants:

rn, l, y, r, rl, n, t, rr

Two examples of a word final ly phoneme:

- ly kantjalykantjaly ‘mushroom’ has no natural speech recording.

- ly murily ‘honey’

4.4 Consonant Clusters

The most common consonant clusters of 500 words are listed below. The syllable pattern for each word are either consonant+vowel (176 CV syllables in 100 words) or, less frequently, consonant+vowel+consonant (62 CVC syllables in 100 words). In the instances where a syllable is a CVC pattern, the subsequent syllable will commence with a C and a consonant cluster will occur. For example, jintu jin/tu, the consonant cluster nt is formed due to the syllable pattern. However, the phonemes are not pronounced together as in the English word ‘ant’ but are pronounced according to the syllable they belong to.

| nt | jintu | jin/tu | ‘hair’ | ||

| ntj | wintju | win/tju | ‘wet’ | ||

| np | yanparra | yan/pa/rra | ‘self’ | ||

p | kalpi | kal/pi | ‘back’ | ||

| lt | kaltu | kal/tu | ‘cut’ | ||

mp | kampa | kam/pa | ‘burn’ | ||

rp | kurpit | kur/pit | ‘grey’ | ||

ngt | yungtal | yung/tal | ‘daughter’ | ||

| rk | marku | mar/ku | ‘witchery grub’ | ||

ltj | waltja | wal/tja | ‘eagle hawk’ | ||

| rnt | warntu | warn/tu | ‘clothing’ | ||

rp | marparn | mar/parn | ‘witch doctor’ | ||

rlk | warlka | warl/ka | ‘sandalwood’ | ||

rlt | warltanara | warl/ta/na/ra | ‘stripe’ | ||

lk

| wilkara | wil/kara | ‘lift’ | ||

| Nasal stop | n+t

m+p

n+tj

n+p | jintu = jin/tu ‘sun’

kampa = kam/pa ‘burn kuntja = kun/tja ‘whiskers’

murrunpu = mu/rrun/pu ‘bush’ | |||

| Nasal alveopalatal | n+j | nyinji = nyin/ji ‘spear’ | |||

| Nasal nasal | n+m | nyinmarra = nyin/ma/rra ‘dog’ | |||

| Lateral nasal | ly+n | wirrilyn = wi/rri/lyin ‘spill’ | |||

| Lateral stop | l+p

l+t

rl+k | kalpi = kal/pi ‘back’

kaltu = kal/tu ‘cut’

jirlka = jirl/ka ‘spike’ | |||

| Lateral dental | l+j | milji = mil/ji ‘nail’ | |||

| Rhotic stop | r+k

rl+k rn+t r+p rl+p | karkarri = kar/ka/rri ‘drunk’

marlkurr = marl/kurr ‘come back’

marnti = marn/ti ‘little boy’ paarpakan = paar/pa/kan ‘flying’

tarlpu = tarl/pu ‘dislike’

| |||

| Rhotic nasal | rl+m | marlmarla = marl/marl/a ‘dip’

| |||

| Glide nasal | y+n+m |

minyma = miny/ma ‘woman’

| |||

| Lateral glide | l+y | murily = mu/riyly ‘young’

| |||

The ‘ng’ phoneme is pronounced as ‘ng’ in singer not as in finger. The latter would be written as ‘ngg’ in Maduwongga as both the ‘n’ and ‘ng’ are pronounced.

4.5 Geminate

There are three words occurring as geminate:

- pannangurru ‘other side’ (of the hill)

- kannala ‘kangaroo’

- nunnga ‘woman’

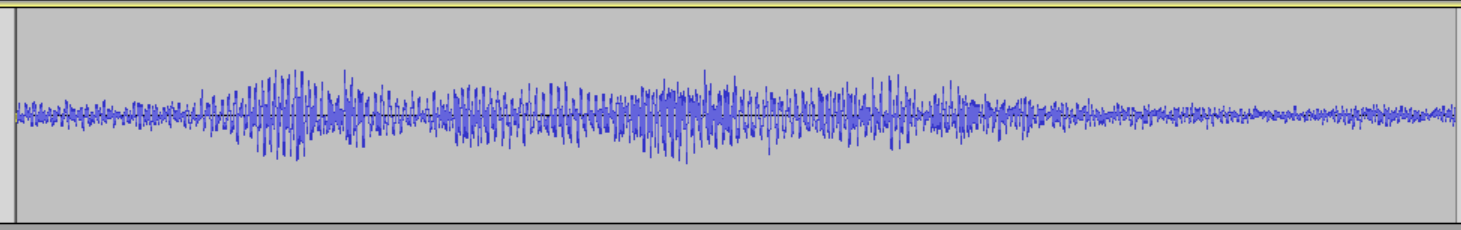

5. Minimal Pairs

| l – ly | ngala ‘eat’ | ngalya ‘face’ |

| l – n | nganala ‘rock wallaby’ | nganana ‘what’ |

| l – rr | tjungulin ‘small’ | tjungurrin ‘come together’ |

| l – r | kutjala ‘cook’ | kutjara ‘two’ |

| a – i | kata ‘head’ | kati ‘spear’ |

| i – u | kati ‘bundle of spear’ | katu ‘on top’ |

| tj – t | katja ‘son’ | kuta ‘brother’ |

| u – i | tjutju ‘sister’ | tjitji ‘child’ |

| n – t | nangana ‘this’ | nangata ‘here’ |

| tj – r | yamatji ‘friend’ | yamari ‘forearm’ |

| ng – rl | wangka ‘talk’ | warlka ‘sandalwood’ |

| tj – t | yarltji ‘how is it?’ | yarlti ‘call’ |

tj – t

katja ‘son’ Click on the word to hear it.

kurta ‘brother’ Click on the word to hear it.

maayarlti ‘call’ Click on the word to hear it.

yarlji ‘how is it?’ Click on the word to hear it.

u – i

tjutju ‘sister’ Click on the word to hear it.

tjitjipirni ‘children’ Click on the word to hear it.

6. Homophones

Among 500 words two homophones occur.

nyinji ‘white’ and ‘spear’

jintu ‘hair’, ‘frost’, and ‘sun’

7. Stress

As per Goedemans’ 2010, a survey of stress in Australian languages, ‘in an overwhelming majority of Aboriginal languages main stress appears somewhere at the beginning of the word. The prototypical stress pattern for these languages places main stress on the first syllable and secondary stress on alternate syllable thereafter.’ Maduwongga shares the most common pattern, with initial main stress, and secondary stress on the third syllable in longer words.

8. Reduplication

The speaker tends to use reduplication of verbs when she is talking about continuous actions mostly in the past. It is not certain yet to describe those reduplications as indicative of any tense or aspect. To date, Maduwongga has three reduplications derived from a noun, a verb and a descriptor. The rest ten reduplications do not have semantic value if they are not reduplicated.

E.g.:

| Reduplication | Root Word | Gloss |

| maramara | mara ‘hand’ | ‘crawl’ derived from the noun mara and verbalized |

| karpikarpirnu | karpi ‘tie up’ | ‘kept tying up’ derived from verb karpi and it indicates continuous action |

murrunmurrun | murrun ‘murrun bush’ | ‘short’ derived from noun murun and used as a descriptor |

martamarta | marta ‘no semantic value’ | ‘stop urgently’ |

narrinnarrin | narrin ‘no semantic value’ | ‘causing problem’ |

ngaringari | ngari ‘no semantic value’ | ‘hanging around’ |

wapirnwapirn | wapirn ‘no semantic value’ | ‘go mad’ |

nyurinnyurin | nyurin ‘no semantic value’ | ‘curly’ |

tukutukuna | tuku ‘no semantic value’ | ‘huge’ |

parkaparka | parka ‘no semantic value’ | ‘bush berry’ |

| wirruwirru | wirru ‘no semantic value’

| ‘hard, not soft’ |

kalaykalay or kalikali | kalay ‘no semantic value’ kali ‘no semantic value’ | ‘chin’ has no natural speech recording |

kantjalykantjaly | kantjaly ‘no semantic value’ | ‘mushroom’ has no natural speech recording |

9. Onomatopoeic

Only one word in 500 words is onomatopoeic.

pirrirr ‘wind’

10. Haplology

One example of haplology occurs:

ngala ‘eat’ – ngalkun ‘eating’

11. Elision

No elision occurs among 500 words.

12. References

Nudding, Anne Joyce. Recordings with Goldfields Aboriginal Language Centre 2017

Garnier Jules Vocabulary of the Indigenous People of Western Australia

Tindale N.B. Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits and Proper Names (1974)

Goedemans Rob. A Survey of Word Accentual Patterns in the Languages in the World (2010)